Stanford Live has released its 2017–2018 calendar. Highlights include renaissance man Taylor Mac; the Sachala Ensemble from Pakistan; The Stradivarius Ensemble of the Mariinsky Orchestra, under the baton of Valery Gergiev; an evening with Samantha Bee; Renee Fleming; a tribute to Leonard Bernstein; and a conversation with Claudia Rankine, the poet and 2016 MacArthur Fellowship winner, talking about “Whiteness’ and the culture of nostalgia in America.

More than 60 performances are scheduled for the season, which begins in the fall and runs through the middle of next May. The schedule is designed to allow other events to be included at the last minute.

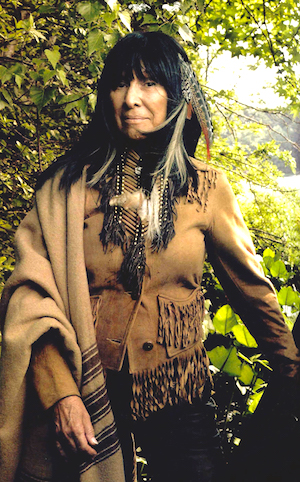

The lights dim on September 22, with Buffy Sainte-Marie, the Canadian folksinger and activist, now 76. She’s a Cree Indian and for many fans the voice of native peoples. That she is Canadian as well as a political figure, reflects the desire of Stanford Live Executive Director Chris Lorway, also Canadian, to frame the coming season — his first — around the idea of identity, in all its guises.

“I’m opening the season with Buffy Sainte-Marie,” Lorway told us the other day, sitting in his economy-sized office at Stanford, and just a quick walk from the Bing Concert Hall, where almost all the events will be held. “I thought, you can’t really talk about ‘nation’ and ‘identity’ without addressing the indigenous first nations.”

The Canadians Are Coming. The Canadians Are Coming

Lorway, 43, is part of the Canadian new wave at Stanford: University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne is Canadian, and Jaroslaw Kapuscinski, associate professor of composition in the music department, spent several years at McGill University. Lorway himself has a classic Cardinal persona, the slightly buttoned-down man whose signature as a manager and a “creative” is top-down, and above all, to put context first, to establish the concept, then open a dialogue with other curators and stakeholders.

“If I’m going to bring in Joshua Bell, for example, the first thing I think of is what does his performance mean? What are the thematic links? The strategy is to leverage anchor performances.”

And if the construct, the journey that Lorway envisions for an entire season, isn’t clear to the audience, particularly after seeing just one performance, then no matter. Lorway’s conviction is that if you stay with him you’ll understand and come away with an appreciation of the grand design. And the revelation that might come with that.

“I completely reject the notion of audience as a singularity, because everything we do, even within a genre, has a specific audience attached to it. Naturally, there might be some crossover.”Lorway’s background is in the festival world as well as in marketing research and analytics. He was appointed in July 2016, and has begun an aggressive campaign to develop new audiences.

“I completely reject the notion of audience as a singularity, because everything we do, even within a genre, has a specific audience attached to it. Naturally, there might be some crossover.”

He added, “I think that’s one of the mistakes a lot of people make when thinking about particular audiences. For example, when you look at a classical audience and you say you want to introduce more new music: To assume the classical music audience is going to follow you is not necessarily the right way to think about it. It’s more about how you find an audience for new music. That might not even be the classical music audience.”

Lorway also believes the so-called “indie” audience is larger than it might seem, but only gathers with certain inducements. He gave the example of putting together a concert honoring Steve Reich on his 80th birthday party. The event was held at Massey Hall in Toronto, in April 2016. Reich had come to Toronto before and usually played at Koerner Hall, which has 1,135 seats. Reich had drawn well in that space, but Lorway thought the indie audience was bigger than it seemed and sought to convince Lawrence Cherney, his collaborator and the artistic director at Soundstreams, to put the concert in Massey Hall, which has 2,752 seats.

“I told him I thought our indie audiences would double, and I was willing to take a financial risk to test that out. I said, ‘I will guarantee the risk up to the first 1,000 seats,’ which is about the number at Koerner Hall. Sure enough, we sold 2,300 seats.”

But what about conversion rates, which are historically low when trying to bring indie audiences into classical music halls, especially after a single concert? That’s been the experience at SoundBox, the San Francisco Symphony’s experiment in building new portals to the hall.

“You can’t expect conversion from one concert,” said Lorway. “But then, I don’t think it’s a matter of building one consistent audience anyway — because the more people you bring in across communities the better, even if they only come once or twice a year, or even once or twice every two years. If they have positive memories of being in your space, then they become advocates for you in the community.”

In the end, said Lorway, “If conversion rates are low, it’s because you’re only offering the conventional experience.”

Bringing Down the ‘Fourth Wall’

Lorway’s mantra, and increasingly that of impresarios across the country, includes not only the necessity of cultivating niche audiences but also changing the “atmospherics,” literally and figuratively, and above all, recasting audience expectation.

In 2001, Lorway was an analyst in a Knight Foundation study of classic music consumption. The study, one of the first of its kind, found that younger people often didn’t like coming to the concert hall simply because of the formalized aspect of the experience. Other dislikes included subscription marketing, “an increasingly dysfunctional paradigm that is often at odds with the goal of attracting younger audiences.” The study concluded that there may be “strategic advantages in loosening the definitional boundaries of classical music.”

For Lorway, you need only look at the history of these forms: “Opera for example, you see how participation has changed. Think of when the great Italian operas were presented. If the soprano sang an aria particularly well, the audience would take control and demand [she] sing it a second time. There was always a give-and-take between artist and audience, but then for whatever reason this wall of conservatism has shut that all out.”

“But I think we’re hitting a point, particularly with the younger generations, where they feel the need to reclaim a level of informality. Of course, that means going through an interesting transition period, because there are still those brought up in the old ritualized style now clashing with those who want a very different experience.”

This different experience is often built around what’s known in the trade as “stadium service,” a euphemism for the ability of a licensed performance venue to allow audience members to bring alcoholic drinks into the hall. Lorway points to Roy Thomson Hall, the 2,636-seat home of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, where this experiment has been going on for some years. Interestingly, it’s the Symphony members themselves who decide, on the basis of a particular program, whether a concert should be open to stadium service.

Another experiment in Toronto includes “Late Night” concerts that begin at 10 p.m. Lorway notes that those have been unusually successful, as have the efforts at cultural merge going on in places like Utrecht in the Netherlands. That city’s new eight-story arts complex features a symphony hall and on top of it a nightclub with a capacity for 2,500. The Utrecht Symphony has set aside Thursday nights for DJs to play to a club audience in the symphony hall, with the symphony in attendance. The evening includes an interview by the DJ with the conductor, along with a movement or two from a classical work. In addition, there’s a lottery for a few seats placed inside the orchestra during a performance. These evenings sell out.

Economics of a Small Hall

If the Cardinal-Bears “Big Game” were held on the cultural gridiron, Cal Performances would win easily, which is a measure of geography, demography, history, an emphasis on community outreach (which has drawn Lorway’s own interest), and, finally, seating capacity. Both schools have more than one venue but the main performance halls best illustrate the point. Zellerbach Hall, a traditional, front facing space, was built on the UC Berkeley campus in 1968, with 2,689 seats. On The Farm, the Bing Auditorium, which is arranged in a “vineyard” format, opened in 2013, with 842 seats.

“I could use another 500 seats,” noted Lorway. “It’s nice to have the number of sold out shows that we have, but it makes the economics more challenging.”

As for the notion of a cultural Big Game he replied, with trace amounts of chagrin, “I don’t approach things that way. I’ve always worked on an international scale. My interest is to carve out and leverage the relationships I have built up to bring a level of international discourse and excitement to Stanford, which I think I can do pretty easily.”

For Lorway, the key question is always, “Are you programming things that students are actually interested in seeing?”

"You’ve got all these people working at Facebook, Google, and Apple looking for things to do. It’s the perfect vacuum to fill." For the moment, few Stanford Live performances break even. It’s the irony of most university affiliated performance halls, which cannot exist on student interest alone. About 13 percent of the Stanford Live audience is students, who pay $15 for the pleasure. To increase participation, Lorway is appealing to aspiring music producers to become impresarios themselves. The idea is to enlist a half-dozen students from the Stanford Concert Network. They would be given a break-even budget to choose artists, who would perform, among other places, in the cabaret space at Bing auditorium. No start date has been set.

But there’s another factor in play to Lorway’s advantage. That’s the extraordinary number of Millennials living on the Peninsula, where there’s no real live music scene. “You’ve got all these people working at Facebook, Google, and Apple looking for things to do,” said Lorway. “It’s the perfect vacuum to fill.”

Bernstein and the American Sound

While Stanford Live’s broad ambition this season is to reach a new understanding of identity, Lorway’s means of getting there suggests a conceptualized train that stops at three ideas. One is this new cultural interest in nostalgia, which the likes of Taylor Mac insist is the “last bastion of racism.” Of course, there are other, less political aspects of nostalgia, if only the memories of other times when discourse had more nobility and rebellions were more clearly focused.

Another idea evokes the 150th anniversary of the first British North America Act, which in 1867 brought together the disparate colonies of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick into a single entity within the British Empire. The intent here is to bring in a Canadian perspective, and also, perhaps, a nod to the university’s president.

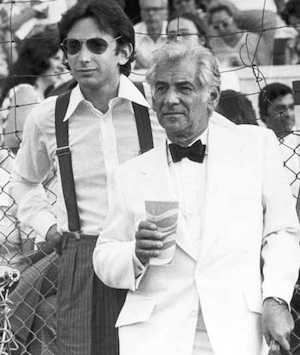

The third idea, and “the central figure in all this,” celebrates the music and activist life of Leonard Bernstein, and his ability to articulate the nature of the “American sound.” For Lorway, who better to demonstrate the nexus between art and politics than Bernstein, with his Harvard education during the Great Depression, with his evolution as a progressive, with his understanding of American music, as both conductor and composer? And then, consider his correspondence and extraordinary friendship with Aaron Copland.

Lorway put it this way, paraphrasing Bernstein’s perspective of his own evolution: ‘When I think of the ‘American sound,’ I’m told as a young composer I need to follow either the second Viennese school or I have to be a neoclassicist and neither of those resonate with me. But when I listen, I hear the simplicity of church music coming into a clash with black music and Latin music. And where those worlds collide, that simple harmony and that rhythmic texture, that’s where I think we have the ‘American Sound.’”

But what precisely is Lorway’s responsibility in this vast presentation? And what is the impresario’s proper role in this era of acrimony? How do you manage the right balance of provocation and traditional, apolitical entertainment?

“My responsibility as a presenter,” replied Lorway, “is actually not to comment myself but to find artists willing to comment in their own particular ways and from a series of different viewpoints.”

No doubt, but in the context of political art does that put the presenter in the role of a publisher who must, in fairness, provide representation from all sides? And how do you do that in this kind of venue?

Lorway, with the quick, open mind of a true impresario, replied, “there’s no reason why we couldn’t, in conjunction with a particular presentation, why we couldn’t bring in other critical voices to debate the other side of an issue.”