With some new works, inspiration comes in a flash. Others develop over a lifetime. As Trimpin prepares to unveil his latest music-theater work at Stanford Lively Arts this month, he says it has been a work in progress for the better part of 50 years.

The Gurs Zyklus (Gurs cycle), which the German-born, Seattle-based composer-inventor traces back to a childhood memory, explores the history of Gurs, a village in the French Pyrenees mountains where thousands of Jews were interned during World War II. Many died there; others were sent on to death camps such as Auschwitz. Commissioned by Lively Arts, the multimedia work evokes the place in an original soundscape integrating live performance, visual imagery, and kinetic instruments. Directed by Rinde Eckert, it makes its world premiere May 14 in Stanford’s Memorial Auditorium.

Trimpin (who was born Gerhard Trimpin but uses only his surname) grew up in the 1950s in the German town of Efringen-Kirchen. He was still a boy when he first encountered Gurs. In a recent call from his Seattle studio, he said he literally stumbled over it while out walking one day.

“I was 8 or 9 years old,” he recalls. “I came across this Jewish cemetery, and I was unable to read the inscription of the gravestones because the symbols were not in the Latin script. That was the first moment: the curiosity I felt, trying to decipher these inscriptions.

“I came home asking, and learned that those were Hebrew symbols and letters. And I learned that people from the local Jewish community were sent to this place in France, to Gurs. For me, that’s where everything started, this curiosity to find out what happened.”

Trimpin says that the incident remained in his memory over the years, even as he built a career as a composer, sound artist, kinetic sculptor, and instrument maker. A pioneer in sound perception and the recipient of a MacArthur “Genius Award” in 1997, he has created an extensive body of work, alone and in collaboration with artists such as choreographer Merce Cunningham, the Kronos Quartet, and Conlon Nancarrow.

It was Nancarrow, he says, who brought the Gurs name back to the forefront of his imagination. Working with Trimpin in the late 1980s, the American composer — who had traveled to Spain in the 1930s, joining the Lincoln Brigade to fight fascism during the Spanish Civil War — revealed that he had been interned at Gurs.

Impelled to Explore a Horror

“He was kind of reluctantly talking about his time in Spain,” Trimpin recalls. “He remembered how, trying to flee Spain and entering into France, they were shocked to be treated by the French in this horrific way — being sent to a beach in February, where half a million people were camping out with nothing, no blankets, just burying themselves in the sand dunes. He talked about being interned in France, and of course Gurs came up. And from that point on, I knew I had to work with this issue.”

Trimpin began developing a new work about Gurs, traveling to France and visiting the site of the camp, taking photographs and developing a sound world to depict the place. And he continued to encounter references to Gurs. He met people who knew the place. He received letters from families whose relatives had been interned there.

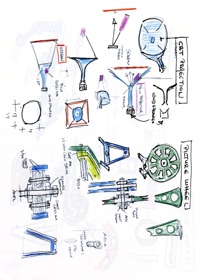

Eventually, The Gurs Zyklus took shape, emerging as a synthesis of aural and visual elements, kinetic instruments, and spatial music. For the May 14 performance, director Eckert will serve as narrator; four vocalists — Thomasa Eckert, Susan Rode Morris, Katya Roemer, and Linda Strandberg — are also featured. Trimpin’s site-specific installation includes conventional instruments (four player pianos, xylophones, recorders, and percussion) plus an array of his own original instruments: a Fire Organ, which uses actual fire to produce sound in glass tubes; a Water Organ, which drips water onto piano strings; and rolling loudspeakers mounted on a 40-foot teeter-totter.

Train sounds and natural elements are employed; visuals are a key component. Trimpin says images of the old-growth trees that surround the camp play a prominent role. “They are still there, bearing witness,” he says.

The work also incorporates music from two of Nancarrow’s piano studies; Trimpin says the composer, who died in 1997, remains a primary inspiration. “There was so much spatial experience in his music,” he says. “It wasn’t just a pitch-time or harmonic configuration. Suddenly also space was introduced in his music. This reminded me of how I was always thinking and listening and seeing. Every time I was listening to a sound, the visual impact was as important. When I was watching something, there was always an aural component, too. It’s just like the wind, or any environmental noises — both were important to kind of comprehend, to focus on.”

All Live

Trimpin, who this month completes a yearlong residency at Stanford, worked with students at the university’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics to develop the Gurs sound sculptures. “Everything is kind of kinetic,” says the composer. “Nothing is faked. There’s no electronic music, no sampled music. The sounds are all coming live from these instruments.”

I ask Trimpin about the students’ reactions to the work. “I think they have a different relationship to these elements,” he says. “But hopefully it will help to raise questions about these people, the letters, about what happened there 70 years ago.” He plans to remount the cycle in Seattle, and may even make excerpts available for streaming. “They’ll be able to access it through their iPhones,” he remarks.

Still, the sound world of The Gurs Zyklus may be best experienced live. For Trimpin, hearing the work in the moment, in the space for which it was created, is essential.

“That’s what my whole lifetime investigation has been: acoustical sounds, or sounds coming from a source,” he says. “It’s a completely different experience for the audience, because your body will be confronted by the vibration coming from these elements. As soon as it’s synthesized or coming from an artificial source like a loudspeaker, the body doesn’t respond the same way. It actually affects your senses differently.

“That’s what I hope in the Gurs Zyklus, that the audience will experience certain kinds of movements, acoustical movements, so that not everything is explained from the narrative. It’s helping to get the audience to make their own interpretation of what they’ve just experienced. That’s always what I hope happens with an installation: that the audience will walk out feeling they’re just had a different experience than just a regular concert.”