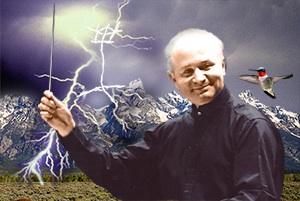

Photomontage by Jeff Dunn

I’ve always been fascinated by thunderstorms; they’ve influenced many of my works. ... I remember lightning flashes I’ve seen. There was one in the Tetons, in the middle of the day. Vile, black-gray puzzle clouds surrounded the mountains. A storm erupted, a big one. I was viewing it from outside. There was a lightning flash, a ground-to-sky one. This lightning flash came back from the sky, and it didn’t seem to know whether to go to the peak on the right or the peak on the left. So halfway down, it split in two. And one of its forks hit bang center one of these giant peaks, and other one hit the other peak on the other side, making, like, three toes — like a music stand!Even just a photograph of lightning was enough to generate one composition, Ringed by the Flat Horizon, one of the composer’s six works to be featured as part of the Phyllis C. Wattis Composer Residency/Project in San Francisco.

I saw before I came to America a photograph in a book of the New Mexico desert completely flat — absolutely flat — and in the background an immense storm approaching with its shadow of vertical rain and, bang against that, almost perfectly vertical, a sky-to-earth flash-bolt of lightning. This ominous, mysterious, evocative photograph absolutely played into my obsession with thunderstorms, their atmosphere, their sounds, their display of lights, their sense of rhythm, and their sense of form. Ringed by the Flat Horizon is not a tone poem, but it’s very much, I hope, evocative of the experience of storms. It’s an abstract musical piece, but at the same time I hope it’s suggestive beyond the concert hall, and maybe into the desert.

Benjamin will turn 50 on Jan. 31. The native Londoner has a celebratory year cut out for him, with performances in several cities in the U.S. and Europe, including a stint as music director of the Ojai Festival in June, where his frightening chamber opera about the Pied Piper, Into the Little Hill, will receive its first West Coast performance.

He has been described by New York Times critic Anthony Tommasini as “one of the most formidable composers of his generation,” his music “bursting with personality.” His “feeling for French sonorities” comes from his studies in Paris, while a teenager, with Olivier Messiaen, one of the greatest composers of the last half of the 20th century. The critic Paul Griffiths described one of his pieces as “bringing into an airy Ravel-Debussy world a Mahlerian sense of the composer’s emotional self.”

Benjamin also impresses critics with the meticulousness and clarity of his music. He takes pains not to repeat himself, so each work seems to solve a new problem in a fresh manner, making him one of the more original — though least prolific — of the major composers working today.

Cinematic Epiphany

Although he had been taking piano lessons, Benjamin was not interested in classical music until he had an epiphany while seeing Walt Disney’s Fantasia at age 7. As he describes it in a published biographical sketch,That was a decisive moment. On my way home after seeing the film, I bought a record of Beethoven and then even threw all my 45s into the dustbin. From that moment on, I knew what I wanted to do: compose music. It was a total conversion. From then, from the ages of eight to ten, I was interested in only one thing, with the kind of crazy enthusiasm that a child might have for a football team, except that for me it was for Beethoven. I bought scores and records, and even wrote booklets, which I illustrated.

At the Paris Conservatoire, Benjamin became fascinated with the nature of harmonies. “Each week, I played two hundred chords on the piano, and [Messiaen] would listen and criticize them.” But when Messiaen retired in 1978, Benjamin transferred to Cambridge University. His teacher there was Alexander Goehr, a follower of Arnold Schoenberg and the 12-tone/serial school. “We discussed a great deal. I was respectful, but it was sometimes quite tense. However, it made me think a lot and I think it liberated me from Messiaen’s influence.”

In 1980, Benjamin published Ringed by the Flat Horizon, his first orchestral work. It brought him immediate recognition as a force to be reckoned with on the contemporary scene, and will be paired with one of his latest works, Duet (2008), in the San Francisco Symphony program of Jan. 14-16. Benjamin himself will conduct his music, along with that of Ravel and Messiaen.

The Symphony publicists label Duet a piano concerto, though Benjamin quickly corrected me on that characterization:

It’s so much not a piano concerto. I deliberately did not call it a concerto. It’s a “duet” between piano and orchestra. The reason being that I’m not a great fan of the standard concerto format. I have a problem with the idea of the orchestra either doubling or overwhelming the soloist right in the foreground. ... I don’t like rhetoric, the hero against the massive orchestra. I don’t like the idea, and I don’t like the sound, either.David Robertson, music director of the St. Louis Symphony and a strong advocate for Benjamin’s music, will conduct the first program of the series Jan. 7-10. Along with music of Debussy (except for the Friday 6.5 concert) and Mendelssohn, this concert features Benjamin’s Jubilations and Dance Figures. Benjamin himself is looking forward to it:The problem is that the sound of the piano dies. It dies the moment you strike it. And it dies incredibly quickly at the top, yet the lower notes can last a very long time, even though they’re dying the moment they’re struck. No other instrument apart from the harp and pizzicato and percussion has that sound reality in the orchestra. These other instruments play lines, they breathe, they sustain. They have living dynamics. The piano, in contrast, has a pedal. No orchestral instrument has anything like it. The piano can play ten-note chords. No orchestral instrument can do that. The piano covers seven and a half octaves with a basically homogenous tone quality. No orchestral instrument approaches that. They’re extraordinarily different.

The piano was growing to become a sort of replacement orchestra, an orchestra in black and white, in the 19th century. The problem is that when you put the real orchestra against this black and white orchestra, you have to come up with tricks to make them work together, unexpected devices, although to my ears, it can sound like two roles that have nothing to do with each other.

It is a new sonority. It doesn’t sound like what a concerto’s meant to sound like, that’s for sure!

Gigantic Musical Celebration

[Jubilations] is a piece I haven’t heard for about 15 years. One reason is that it requires gigantic forces. It was written for the London Youth Orchestra, and it’s a celebration of youthful music-making, where the orchestral part is not particularly virtuosic, but there are also many extra groups added to the orchestra, all intended to be played by children, such as extra percussion and brass, massive recorders playing rather virtuoso lines, a steel bands group, and important synthesizer parts. If you use everything that’s possible, and in large numbers, it can easily go to 250-300 performers.As for Dance Figures,But it’s not like Cecil B. DeMille. It’s actually quite delicate because I wanted each of the groups as they enter to have the spotlight on them and be distinctly heard, so massive sounds are fairly rare except at the end of the piece. It’s like a slow processional, where one by one, each of the groups enters, has their moment, sometimes combines, then passes it on to another group.

It’s like a journey through a series of short stories. The longest is only about four minutes. Some of them are very delicate and gentle. A few of them are extremely noisy and energetic. If you’re prepared to accept the nonsymphonic nature of the structure, that it’s made of self-contained statements, then it’s a piece that maybe can speak more quickly to a listener than some of my other works. It’s simple in approach and very direct in its moods.

Robertson is enthusiastic about the opportunity to conduct Benjamin’s music here.

George’s music really doesn’t sound like anyone else’s. When you hear his works, they can combine simplicity and sophistication in a way that very few other composers in the 20th or the 21st century have been able to do. [What strikes me about his music] is its historical underpinnings. It’s really very informed about all the music in the Western canon, from plainchant on out. That means that it’s like a really fine writer, like [Jorge Luis] Borges. It’s absolutely his prose, and yet you know that he has everything — from Homer and the Bible, through Shakespeare and Goethe and Cervantes — all of this in his mind when he’s writing. And so what comes out is this writing that is both very unique and original and yet extremely rich in the field of words, and this is how George’s sounds work in the field of music.

Benjamin’s visit here will conclude with a chamber concert on Jan. 17, which will include his Viola, Viola and Piano Figures, the latter played by the composer himself. Benjamin tells me he’s excited to be here again, so some of that energy will undoubtedly rub off in his performances in San Francisco:

It’s a beautiful city. And the bridge — ah! — the bridge. It’s so marvelous. My first visit, I was staying in Berkeley, and I remember the beautiful weather, and the light. I saw my first-ever hummingbird in Berkeley. We don’t have them in England, so this sensational beast was a great moment for me.

Maybe Benjamin’s visit will provide sweet, previously untasted nectar for many audience members.