Over 60 years after his death in 1959, Heitor Villa-Lobos is still best-known for a single movement in a single composition, the haunting Aria from the Bachianas Brasileiras (“Bach-inspired Brazilian pieces”) No. 5, with the wonderful, chug-chugging Toccata from the Bachianas Brasileiras No. 2 (aka “The Little Train of the Caipira”) in second place. That’s just the tiny tip of a huge iceberg of music, over 2,000 compositions in virtually every genre (even a Broadway show, Magdalena), along with a number of categories that he invented himself.

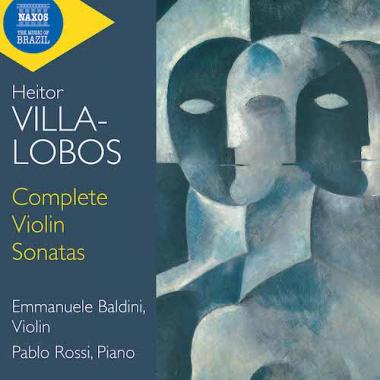

But before anyone hails the three Villa-Lobos violin sonatas — as recorded by violinist Emmanuele Baldini and pianist Pablo Rossi on Naxos’s enterprising The Music of Brazil series — as major discoveries, note that these are not the first recordings of these works, and they are not prime Villa-Lobos in any case.

The sonatas come from an early stage in Villa-Lobos’s career, 1912 to 1920, when he was still assimilating European Romantic influences, particularly from France. The Sonata Fantasia No. 1 bears the subtitle Deséspérance (“Despair”), and it starts with a melancholy and yes, despairing theme on the violin before the piano steps in to break up the rhythm. There are bursts of agitation in the center and near the end of the single movement piece, but the basic down-in-the-dumps mood doesn’t change. It sounds thoroughly European, with not a trace of the Brazilian tinge that would infiltrate his music later.

Even though the musical language is changed somewhat, becoming more sophisticated and more varied in mood, I don’t hear the Villa-Lobos personality in the Sonata Fantasia No. 2 or the Sonata No. 3 either — save for one syncopated measure in the first movement of No. 2. The slow movement of No. 2 is very pretty — a long, lyrical song for violin with an impassioned climax. Any number of composers living around the year of Villa-Lobos’s birth (1887) could have done something like it.

The Sonata No. 3 moves up the French timeline toward Debussy in its harmonies and hints of a whole-tone scale in the first movement, and the Allegro vivace scherzando movement has capriciousness going for it. By 1920, the year of the third sonata’s composition, Villa-Lobos had already begun to incorporate the influences of his homeland into his orchestral works, but not here.

As heard via stream, the performances are accomplished and smooth — and I suppose these works make decent vehicles for violin-piano duos who want to freshen up their repertories. But for someone who wants to dive into Villa-Lobos’s extensive chamber-music stock for the first time, I would recommend starting with the string quartets — particularly the middle ones (Nos. 5 through 9) that are full of the composer’s unique personality as he roams from Brazilian tunes and rhythms to flirtations with neoclassicism and dissonance. He wrote 17 of them, and there’s not a cull in the bunch.