The 20th anniversary of the formal dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was on Dec. 31, 2011. It was not an anniversary much marked in this country, except among Soviet expats, but it provides some background to the Pacifica Quartet’s most recent recording.

A number of arts organizations in Chicago have collaborated for years on a project called “The Soviet Arts Experience.” To me, philistine that I am, that suggests a theme park, wherein you get a taste of the gulag, but also get to leave anytime you want. (Next up: The Cultural Revolution Arts Experience? The Third Reich Arts Experience? The Juche Arts Experience?)

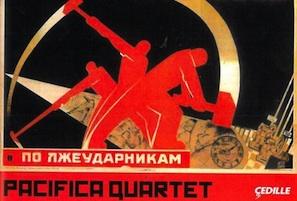

I am not comforted by the booklet notes’ reference to the “stunning, hand-painted propaganda posters” that are part of the three-year project. The one on the cover of the Pacifica Quartet’s new two-CD set is from 1931, and titled “We Smite the Lazy Worker.” The only thing in that poster that looks human is the person whose head is about to be smote in. The “We” of the title are anonymous crimson bipeds, with crimson sledgehammers.

Listen To The Music

Shostakovich String Quartet No. 5 - I. Allegretto Non TroppoMiaskovsky String Quartet No. 13 - I. Moderato

All of which is a most unfair setting for the Pacifica Quartet’s project. They have played the entire Shostakovich quartet cycle, and will be recording all of it. The particular slice they chose for the first installment is the canniest move I’ve seen a quartet make in some time. The usual way to record Shostakovich quartets is to do the Eighth, and then anything else you feel like; or else to record them all at the same time. The Pacificas, whom I darkly suspect of engineering all of this, have recorded, as their first installment, four Shostakovich quartets, in strict chronological order (with the Eighth the last of the four), with Nikolai Miaskovsky’s last thrown in as bonus.

Now, this is brilliant: You can’t really get a better idea of whether you like Shostakovich or not than from that particular set of four pieces, and it looks like the Eighth is just there by chance, which it can’t be.

No. 5 is a lanky, discursive thing, with — news to me, but it’s from the exceptionally fine program notes by William Hussey — a repeated quotation from a trio by Shostakovich’s student Galina Ustvolskaya, a work not to be published for almost two decades, and so practically the ultimate in-joke.

No. 6 is jolliness itself, until it is not. It’s one of those Shostakovich pieces with a passacaglia-based slow movement and finale — that is, there’s a line that is always there, whatever else shifts above it — and then that line comes back in the next movement. (The third and tenth quartets also do this; the first violin concerto does it, too.)

With the Sixth Quartet, you are all in merry territory (apart from the passacaglia slow movement) until the passacaglia reprise kicks in, in the finale. Then you have momentary panic, but you get over it, as soon as that soothing cadence, the one that ends all four movements in that work, puts you nicely to bed.

The Seventh — for my money, the best quartet of Shostakovich’s 15 — is the shortest of them, and the one that wastes least. There isn’t a note there that oughtn’t to be, which isn’t something you could say of Shostakovich in general.

And the Eighth? If you have not heard the Eighth, you likely don’t go to string quartet concerts, buy string quartet CDs, or play a stringed instrument. It’s the Shostakovich quartet for people who don’t play, or listen to, any other Shostakovich quartets. Formally dedicated “To the victims of Fascism and war,” later widely interpreted as an indictment of the totalitarian system the composer lived under, it doesn’t work very well in either capacity. There is still something queasy-making in the spectacle of a composer putting his own tragedy (spelled out as DSCH, and in numerous other self-quotations) at the center of a work, when he was still alive and so many of his less-careful contemporaries were dead; and packing it all into a string quartet, with all its connotations of intimacy, but with (given time, place, and manner) the prospect of many public performances.

That said, it’s a great work, all the more so (I think) if you don’t know its background, as most audiences in this country do not.

Nikolai Miaskovsky is getting the tail end of this review, which is unfair. Miaskovsky (also, and more frequently, transliterated “Myaskovsky”) is the outlier here; he was born a quarter century before Shostakovich was, and so was almost middle-aged when the U.S.S.R. was formed; he lived long enough to be condemned as a “Formalist” in 1948, but not long enough to be exonerated before he died, in 1950.

The 13th Quartet was very nearly the last thing he composed, and, judging by concerts and recordings I’ve heard, it occupies a special place in the hearts of ex-Soviet citizens who play string quartets. (I’ve heard and reviewed two live performances, and this isn’t the first CD recording I’ve heard; that would be meaningless, except that I haven’t heard any of the other 12 Miaskovsky quartets, live or recorded.)

It’s a marvelous work. I doubt anyone would place it at mid-20th-c., but why should they have to? That slow movement alone is a priceless thing, whatever its decade.

The Pacifica Quartet, throughout, is magnificent. Not as muscularly American as the Emersons; not as cold as the Borodins; just impeccably balanced, fantastically controlled, and in this for the long haul, which is the best news of all.