Jules Massenet’s opera Werther bursts at the seams with thrilling music. He used J.W. Von Goethe’s iconic hero and his unattainable love, Charlotte, to revel in the intense feelings of longing and despair that power so many Romantic operas. It hardly matters that Goethe holds the title character at an ironic distance; Massenet embraces him and gives Werther music of a beauty so ravishing that it suspends any ironic impulse, even when despair leads to suicide.

Photos by Cory Weaver

So it is unfortunate that the San Francisco Opera’s current production adopts Goethe’s distance, working against so much of what Massenet does with the music. On the other hand, it boasts an extremely strong cast, headed by Ramón Vargas and expertly conducted by Emmanuel Villaume. Everyone should hear Villaume’s stunning ensemble of singers and players.

This is a tenor’s opera, with a lot for the hero to sing. Vargas, a veteran in the part, revealed a lovely, gentle tone along with subtle and convincing acting and showed a fine understanding of the French style. His voice occasionally seemed underpowered, however, and some high, soft notes showed strain.

Charlotte, a mezzo-soprano, must move by stages from quiet restraint to an unrequited lover in full awareness of her passion for Werther. Only at her great turning point, just before Werther’s Christmas return in Act 3, does she gush with tears, as her restraint collapses. This brief aria (“Les larmes qu’ on ne pleure pas” — “The tears one does not weep, fall within our souls”) is a high point of the mezzo repertory, marvelously sung in this staging by Alice Coote.

Coote may have shown too much modest aversion to Werther early on in the evening, but she unfolded and, in the great moments of the last two acts, brought her perfectly focused tone, supple legato, and secure high notes into service, revealing Charlotte’s profound, if hidden, emotional depths.

Charlotte’s teenaged sister, Sophie, is a sparkling counterpoint. The part has always been a showpiece, and Heidi Stober played Sophie with charm, energy, and brilliant technique. Sophie also balances Albert, who first appears as Charlotte’s fiancé and then as her husband. Brian Mulligan, unveiling a strong baritone, played Albert as considerate yet brusquely assured.

Villaume set an elegant pace just right for the French style and brought the beautiful inner parts of the orchestra score to the surface. The orchestra’s excellent leaders played the many exposed passages with sensitivity. On a few occasions, though, the brass jumped out of balance, overwhelming the other forces, not to mention the singers.

Controversial Concept

These musical performances, however superb, were framed by a weird, three-ring circus of a production with added dream sequences, hallucinations, and imaginary activity that undercut the drama. Werther is an intimate work that unfolds in a series of touching vignettes that show middle-class life in rich detail. Charlotte lives simply in her father’s house with a rustic garden, a realm in which she serves in place of her dead mother. Werther falls in love with this world as much as with Charlotte.

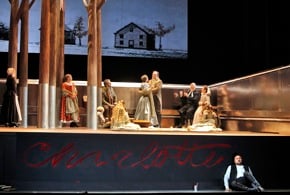

In place of all this, director Francisco Negrin and designer Louis Désiré set the opera on a raised platform some six feet high, occupying most of the stage and surrounded by a low metal wall outlined by neon tubes. Seven abstracted bare trees with aluminum bases tower over the platform. The house is a mountain of packing cases with steep stairs running through them. A large hole in the platform allows awkward entries and exits via an unseen staircase. Werther’s hovel appears at stage level with bed, books, bottles, and, interestingly, a wide-screen TV built into the wall; on it, images of Charlotte appear. The platform places the singers away from the audience, at midstage, and robs the drama of immediacy.

The hallmark of this production is invented action that is no less alien to the spirit of the work than is the constant presence of a hovel. In Act 3, Charlotte should be alone crying over Werther’s letters, but instead Albert is present watching her, and she actually shows the most intimate letter to him; he tears it in half. This doesn’t seem plausible. Still worse, a large bed springs forth for Charlotte and her husband, and when Werther appears (blindfolded and accompanied by two doubles carrying torches), he hovers around the bed, finally eliciting her declaration of love. A dream?

The Act 4 prelude now accompanies an encounter between Charlotte and Werther where they roll on the winter ground and all but have sex. The doubles reappear in time to shoot themselves in the head, along with Werther. Not to worry: A double lies dying while Vargas wanders about singing to Charlotte.

The general effect is of singers caught in a huge piece of conceptual art. We in the audience sit puzzling over what the director may have had in mind, rather than being absorbed by the characters’ emotions. Werther has not been done here for 25 years, and it is not a standard repertory opera. How, then, can those poor souls who have never seen it before possibly understand this show? Some conceptual, nonrealistic productions can produce startling theatrical rewards, even if they are disloyal to the script and score. The assemblage of bright ideas that afflict this Werther, though, could never be accused of that kind of vision and focus.